Should you calibrate a Torque Wrench yourself?

G’day guys,

Today we’re diving into a topic of self-calibrating your torque wrench. Now, I know what you’re thinking—YouTube is brimming with tutorials claiming it’s a breeze, a no-brainer way to keep your tools in check without shelling out for professional calibration. But, let’s pump the brakes for a moment and talk about why this approach might not be the genius hack it’s made out to be.

So first up, lets address the elephant in the room. I have skin in the game here, I own a torque calibration lab, and I am trying to gain your business, so it is in my interest if I convince you not to attempt to self calibrate your torque wrench.

In this blog I will use some screen shots from videos that are freely available over the internet, that encourage the torque wrench owner to self calibrate the tool. The video presenter will usually say that it is a really easy process, and there is no need to send your tools away to be calibrated. I have picked one video at random, but they are a dime a dozen and all usually follow the same erroneous method.

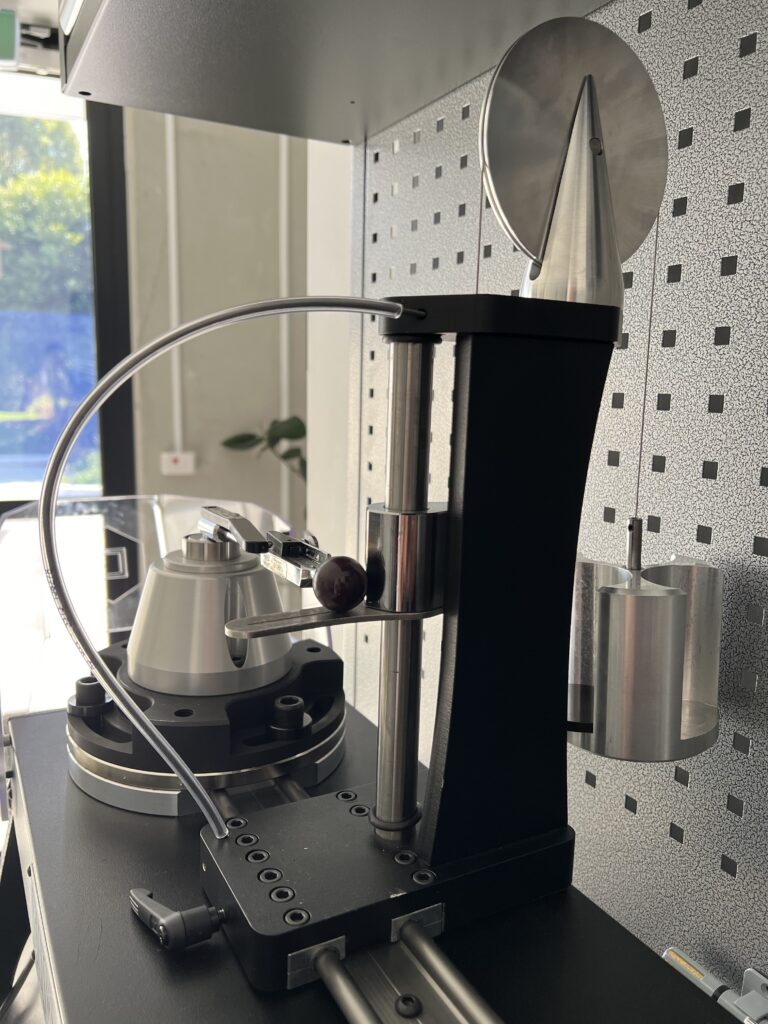

The presenter may advise that if you don’t have a vice, just find a bolt to hang the torque wrench off. This is a really dumb idea as it will increase parasitic forces such as side load. Modern calibration benches that comply to the requirements of ISO 6789 will feature a load balancing device that ensures that the weight of the torque wrench does not become a factor on your results.

In the example below where the torque wrench is being clamped into place by the vice, the weight of the torque wrench is pulling towards the ground due to gravity This essentially preloads a torque on the head of the tool. Think of it as a zero error. If the speedometer in your car was stuck on 20kph when your car is stationary, it is logical to suggest that the speedometer may indicate 40kph when the car is in fact travelling 20kph. In this example, the weight of the tool generates a force, that effectively hides the true result.

The presenter will also usually only have one weight to use to hang from the torque wrench. This only allows calibration at one test point. Remember back to the Torque equation, τ=r×Fsin(θ) where:

- τ is the torque,

- r is the lever arm’s length (the distance from the pivot point to the point where the force is applied),

- F is the magnitude of the force applied,

- θ is the angle between the force vector and the lever arm.

Based on this equation, if we only apply 1 mass to the load point of the wrench, we only generate one amount of torque.

The point is that a torque wrench has a range of operation. i.e. 110nm to 550nm. If we calculated torque only one test point, how can you be sure that the torque wrench is accurate at all settings? Torque wrenches are not always linear in their torque output. The error may be low at low settings, but increase at higher settings. The ISO 6789 Standard calls for tools to be calibrated at 20%, 60%, and 100% of their range. Testing at only one point does not give you any knowledge on how your tool will actually perform over its range, which means you could be under or over torquing your fastener.

Regarding the mass, how do you know how accurate the mass is? Has the mass been calibrated? If you weigh your mass on your bathroom scales, have your scales been calibrated? How do you know that it is accurate? Calibration is a precise science, and any variation in these factors will affect the calculated output. In the example that I refer to, the presenter stated that he was using 7.5kg of weights, but when he weighed them on a scale, they turned out to be 6.559kg. Almost 1kg, or about 13% error straight away. So if you just borrow a weight from your home gym, there is potentially a massive error straight away. Also what about the weight of the rope/chain? It all adds up and is never factored into the torque calculation.

In the example video that I refer to, the presenter then selects a point to hang the weights. He picks an arbitrary point about half way down the handle between the sticker and the “clean bit without any knurling”. That clean bit is the load point. That point is where the load should be applied to ensure accuracy of the torque wrench. Most torque wrenches will have some form of marking or indicator to show the user where the load point is. Any application of force at a point prior to the load point, will usually result in over torquing the nut and bolt. The selection of the load point will be a topic in a future blog.

Also a note on the measuring of the distance, the presenter in this video uses a tape measure to measure the distance between the load point and the centre of the square drive, r in the torque equation. The method the presenter uses introduces another area of uncertainty. Firstly, the hook (the metal right angle bit at the end of the tape) on a tape measure is notorious for working loose. The hook on my personal tape measure is loose and fluctuates probably ± 3mm. Although small in the scheme of things, it is enough to introduce error in your calculation.

Also, when measuring, the presenter does not lay the tape flat against the surface to measure the distance accurately. What the user is actually measuring in this example is the hypotenuse of a right angle triangle, which is the longest side of a triangle. In practice this means that the length that is read on the tape measure is greater than the actual distance between the square drive and load point, which will introduce error and cause the torque wrench to be out of tolerance. It pays to be precise, or your torque calculation will be wrong….

The amount of weight being applied at the load point is most likely not accurate compared to the measured weight, in this case 6.559kg. In this example, the presenter is hanging onto the rope to support the weight to try to accurately record the point that the tool “clicks”. What is happening in reality though is that by supporting the load by hand, the presenter is most likely reducing the amount of weight being applied. If you’re bored and want to experiment, go and try to support 7kg of weight with just your thumb and forefinger and see how accurate you think the weight application is. On the flip side, it is also possible that the DIY Calibrator may also pull on the rope subconsciously which will only increase the weight applied.

And do you remember the Sin𝜽 part of the Torque equation above? 𝜽 is the angle between the force vector and the lever arm. Torque wrenches are designed so that the force is applied at 90º to the torque wrench body. The sin (sine) of 90º is 1. This means that if the load is applied at 90º precisely, mathematically the angle of load application does not affect the torque calculation. But this is not possible in the self calibration DIY YouTube videos. In all cases, when the torque wrench is mounted in a vice, the weight of the torque wrench body causes the handle to lean towards the ground. This means that when a weight is hung from the handle, the load is not being applied at 90º. If you wanted to be precise, you would need to measure the angle precisely and then work out the Sine of that angle, and include that in the torque equation. Of course this is never mentioned…. Obviously this is another source of uncertainty.

Another factor to consider is whether or not the weight is swinging back and forth. If it is, the load applied at the load point will certainly fluctuate. When we hang weight on a calibration beam to calibrate torque transducers in accordance with BS7882:2017, we have to wait not less than 30 seconds for the load to stabilise. Prior to this, the torque readings fluctuate and it is impossible to obtain accurate and consistent results.

As you can see, you cannot apply an accurate weight with this method, thus rendering your torque calculation incorrect.

What about exercising your tool prior to obtaining a reading? All precision equipment must be warmed up and exercised prior to use. An F1 car doesn’t begin a race with a cold engine. An aeroplane doesn’t take off without checking that the engine produces power. In the case of a Torque wrench, exercising a tool 3 – 5 times prior to tightening a fastener, loosens up the internal moving parts and prepares it for use.

I recently ran an experiment on my own Torque wrench where I didn’t exercise the tool. As you can see from the results below, initially the torque wrench was over torquing, however the results stabilised after 4 pre loads. Of course, the DIY Youtube type videos never mention this. If you fail to exercise your tool, you will likely get incorrect results.

Another thing to consider, OHS… What happens if the rope holding the weight slips of the handle and falls onto your toe? Guaranteed to break a few bones I’m afraid.

Without the privilege of putting this particular torque wrench on our calibrator, we will never know just how inaccurate this method was. If I were to take an educated guess though, I doubt this method could calibrate a torque wrench to within 10% of the target torque. Considering that the manufacturers stated accuracy for most torque wrenches ranges from about 2% to 4%, it should be obvious that self calibration simply does not work in practice.

Also it is also vital to understand that if you adjust a torque wrench yourself, you not only void your current calibration (conducted from a professional laboratory), you also possibly void your warranty on your tool.

And finally, probably the most consequential aspect of them all. In this very litigious society that we live these days, in the event a mechanical failure causes damage, injury or worse, any lawyer worth his or her salt will look at all aspects that led to the event. If they can prove that your torque wrench is not properly calibrated by a professional laboratory, guess whose neck will be on the chopping block.

I could go on and on about this topic, but I think you get the idea. Don’t risk it, send your torque wrench to a reputable calibration laboratory!